Optimizing for grades kills passion

What Japanese martial arts can teach us about education and business

Photo by Thao Le Hoang on Unsplash

I peed my pants on my first day of kindergarten because I didn’t know enough English to excuse myself to the bathroom.

A couple of months before that, I couldn’t even draw a straight line. I had just immigrated to the states from a tiny, Indian village.

My dad was the first person in our family (a long history of farmers) to make it out of Gujarat, let alone India. He worked double shifts at Dunkin Donuts while attending community college night classes to become a mechanical engineer.

He made it. That taught me the importance of education. My parents had dreams of me becoming the first doctor in our entire family.

I carried that hope with me for the next 15 years. I obsessed over grades and received instant gratification from my parents when I got As and was punished when I didn’t.

I still remember the look of teary-eyed pride on my mother’s face when I got called in for a special ceremony for getting straight A’s in the 5th grade. Of course, my parents still kept the plaque:

I still remember the day I graduated from ESL to normal english class. I had come a long way from a dirt-eating village boy.

And I still remember the failures. When I got a C in 7th grade English (ugh Ms. Batts 😒), I was terrified. My parents would kill me. I scanned the report card, changed the grade using Microsoft Paint, and printed that out on laminated paper to avoid the repercussions.

It might be hard to wrap your head around this “grade-chasing” concept if you didn’t grow up with immigrant parents. They’ve been surrounded by poverty. They grew up chasing discounts and coupons (and still do), never ate out, and never travelled for leisure. They’ve dealt with risk and instability their whole lives.

So stability—from getting good grades to a high-paying job as a doctor, lawyer, or engineer at a big company—isn’t boring. This is their American dream.

"The most damaging thing you learned in school wasn't something you learned in any specific class. It was learning to get good grades." - Paul Graham (source)

My obsession over grades helped me get accepted to the top state school. And that’s where things started to fall apart.

I fell in love with philosophy and started to hate the focus on rote memorization in my pre-med classes. Rarely did I meet people who loved learning for learning’s sake.

I remember the excitement I had felt walking into the first seminar for “History of the Neuron” deflate immediately when the professor started talking. Every single student around me was viciously banging away on their keyboards — transcribing every word — just in case his comments came up on the first exam.

It felt like I was playing a zero-sum game with smart, talented people all obsessing over GPAs and MCAT scores to inevitably fill a tiny number of capped residency positions.

It was the humanities where I found my true passion.

This all reached an inflection point in my senior year. I dropped out of school and figured I’d find my calling during a “gap year” — I could always finish my last semester afterwards. I was lucky enough to stumble my way into a seminar by Alexis Ohanian at UVa.

His talk changed my life. It was the first time I was exposed to the world of startups, including his experience reading Paul Graham essays and joining Y Combinator’s first batch. I’ll never forget his line: “A hundred years ago, you needed a factory & thousands of workers to start a company. Today, you just need to open your laptop.” But most importantly, I learned that “risk” could be a good thing.

A month later, I was enrolled in Thinkful, a new online school that taught programming with 1:1 mentorship. I loved it and soon hustled my way into an internship—my pitch was effectively cheap labor for a year before I’d go back to UVa and finish up. I never went back.

From day 1, I was thrown into the fire and had to learn everything from programming and sales to content marketing and profit margins. There were no grades. If I messed up, our students would get angry, and we’d lose money. This made me fall in love with learning. Small wins and the encouragement of my teammates boosted my self-confidence.

I felt like Bradley Cooper in Limitless. I vividly remember telling the co-founders, “no one is stopping me from doing what I want here. It’s up to me to learn the skills and prove my value.”

This was a sharp departure from the structured, rigid environment I had been exposed to growing up. Founding your own startup or working for one is typically discouraged in immigrant communities—it involves way too much risk.

About a year into the startup space, I was exposed to Carol Dweck, whose writing captured the transition I had been experiencing: from a “fixed mindset” to a “growth mindset”.

"At the heart of what makes the “growth mindset” so winsome, Dweck found, is that it creates a passion for learning rather than a hunger for approval" (source)

Over-optimizing for a grade or test score kills this passion. It forces you into a mindset where you have to “hack the test” to win.

Chasing higher grades in school translates to chasing a higher salary as an adult.

You go to work to make money, not because you enjoy the work. But when it's your passion, you take the initiative to add your own improvisations and inventions.

Learning for a better grade can’t compare to learning out of curiosity or learning through experimentation. Grade-based learning is anti-failure. You have one chance to get it right each time.

So, what’s a better framework for measuring progress towards a learning goal?

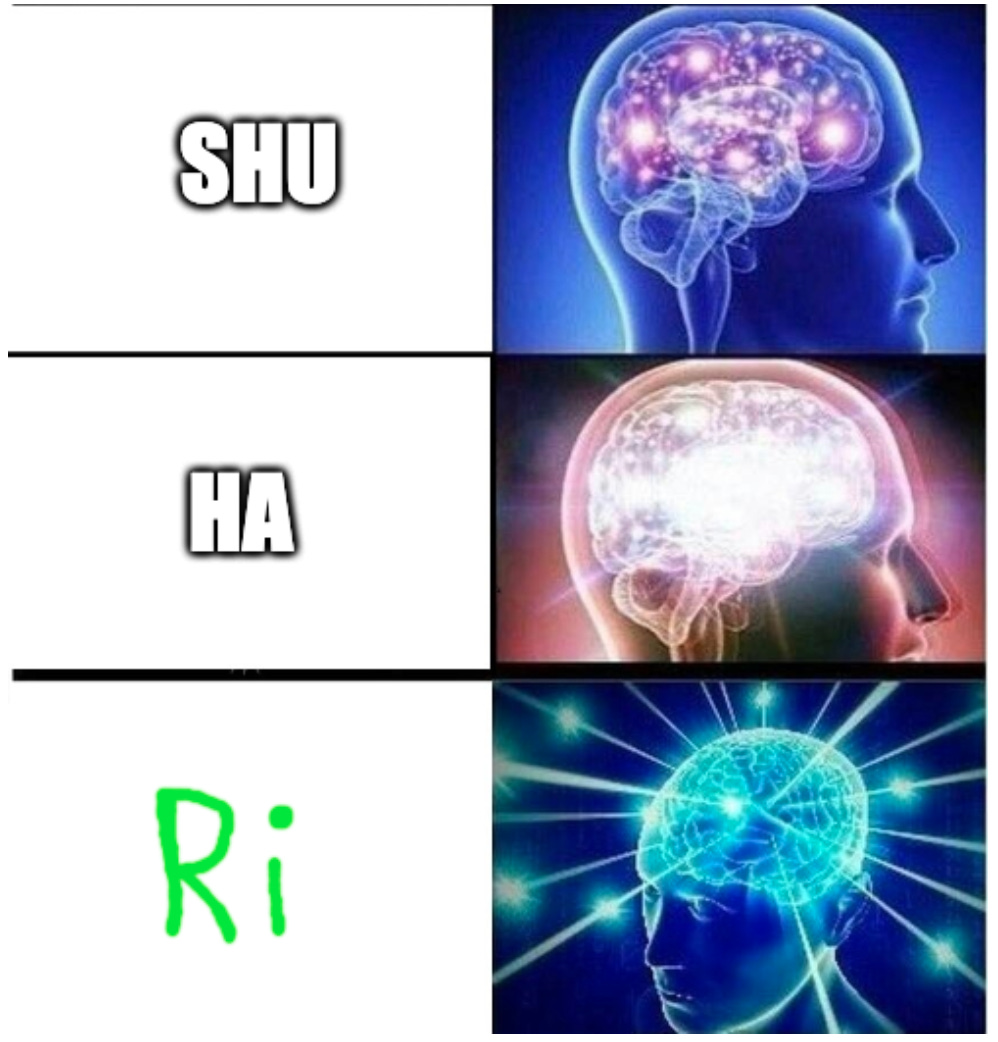

I’ve been recently fascinated by “Shuhari”—a Japanese martial arts concept. It breaks down into three stages:

Shu (守) - traditional wisdom. The student follows the guidance of their teacher precisely. The focus is not on the underlying theory, but how to do the task at hand.

Ha (破) - breaking with tradition. Then, the student digs into the principles behind the technique. She starts integrating insights from other teachers into her own practice.

Ri (離) - transcendence. Now, the student develops her own theory. She can design different techniques to suit her particular circumstances.

Or basically:

The best jazz pianists are excellent improvisers, but learning instruction typically focuses on mastering techniques. In 1987, a group of academics designed a new course leveraging mastery-based learning techniques that yielded strong results. The class mapped perfectly to Shuhari:

Shu: Learning how to play

“Knowledge of the jazz idiom consisted of the ability to define several jazz terms (blues, tritone substitute, etc.), the ability to name five jazz pianists and the ability to interpret several commonly used chord symbols”

Ha: Integrating different techniques

"Students performed a jazz or popular tune of their choice using a walking bass line in the left hand and closed position seventh chords in the right."

Ri: Improvising

“Students improvised on a 12-bar blues in two different keys, a portion of "Lover Man", and a jazz or popular tune of their choice.”

By obsessing over grades (and techniques), you will never reach this “Ri” stage. That’s where the magic of innovation happens.

When I started learning sales and customer development, I’d obsess over scripts and nailing down exact details and delivery. But with hundreds of calls under my belt, I tend to improvise now to drive organic conversation and new insights. I usually re-write entire “scripts” after 2–3 calls.

Can you imagine how terrible it would be if every company thought about sales, design, or marketing the same way?

Roam is an interesting example. For years, the founders engrossed themselves in every single note-taking / knowledge-sharing app (Shu), learned to extract the most compelling ideas (Ha), and then started building heads-down for years.

They built an obsessive cult following, while ignoring most startup / SaaS advice:

Obvious value prop? Nope. Easy to use? Nope. Welcoming brand? Nope. Helpful onboarding? Nope. Intuitive file-and-cabinet structure? Hell no.

Real breakthroughs only happen when you transcend consensus thinking (Ri).

I’ve spent the last 6 years helping adults push past their own misconceptions of what they can and cannot learn. A year after a Thinkful graduate had started his job as a full-time engineer (and purchased a new home!), he shared this:

"You are the first person to believe that I could do this, and because it was you, I believed it. I believed the program because of you."

Sean didn’t need my help. Frankly, he would have succeeded with any school. He was the hardest working student in his cohort. All he needed was someone to believe in him and break past the terrible stigmas about what is and isn’t possible.

Imposter syndrome is very real and a direct consequence of cultural stigma towards risk-taking paired with an outdated education system. This proliferates the “fixed mindset”.

Helping people realize their potential has been and will continue to be a lifelong obsession of mine. Is there something you've always wanted to learn but felt like you couldn't? Maybe it was your method that failed, not you.

Special thanks to the Stew Fortier, Dan Hunt, Frédéric Renken, Danny Keller and Nathan Baschez for feedback.

My next post will be the first of a 2-part series on leveraging social dynamics to build tight-knit learning communities online.

Subscribe to stay updated :)

Terrific post and ideas. Good to be following you here, too.